By Michael Geib

The following article sample was reprinted from American String Teacher, vol 74, issue 4 with permission from ASTA and the author.

Modern double bassists are often confronted with a myriad of choices when playing the instrument. Do we sit or stand? Should we play an instrument with a rounded or flat back? Do we need a C-extension? However, these choices pale in comparison to the following: French or German bow? Unlike our modern bowed string compatriots, double bassists have overhand and underhand bow hold options. The bow is vital to everything in the string family, and before double bassists can even get started, they have to make a choice that will ultimately affect everything about their playing. To this day, this choice can be misinformed and is ultimately influenced by the bow hold of the teacher. In this article, we will explore the advantages and disadvantages of each type of bow hold. This information is intended to aid both classroom instructors and private teachers in making the best bow choice for their double bass students.

French Bow (Overhand Hold)

The French bow hold is similar to that of the violin, viola, and cello. However, there are some unique aspects of the overhand bow hold for double bass:

I. The French double bass bow hold requires more weight to produce a clear sound .

II. The stick is shorter than that of the violin, viola, and cello bow.

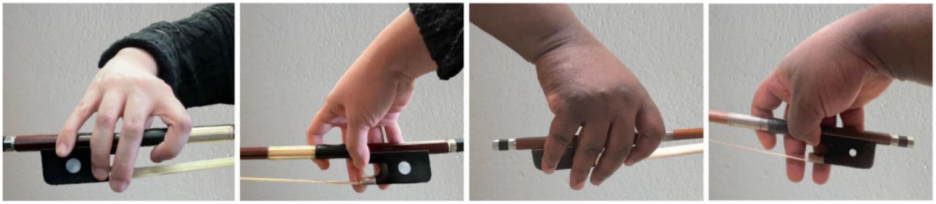

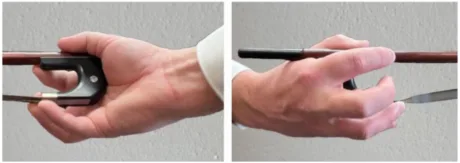

III. Thumb placement is highly variable (see images below):

Figure 1. The “textbook” thumb placement is similar to that of a cello, resting on the underside of the stick just outside the mouth of the frog.

Figure 2. Some double bassists place their thumb towards the back of the mouth of the frog, to allow for more weight to be placed on the bow.

Figure 3. Double bassists of the Italian school take this a step further and simply place the pad of their thumb near the button of the frog.

Figure 4. Some modern double bassists place their thumb under the stick, slide it next to the outside of the mouth of the frog and then touch their middle finger.

These thumb variances are presented not to discourage the learner, but rather provide different options to solve common bow hold problems. Since the German bow is an alternative option, it can be tempting to simply disregard the French bow at the first sign of trouble. I have found that many of my own students who truly prefer the overhand grip can find a comfortable bow hold when experimenting with the aforementioned thumb placements.

French Bow Advantages

I. Similar to the bow grips of the violin, viola, and cello.

II. Execution of articulations is similar to that of violin, viola, and cello in an orchestral setting (spiccato, sautillé, etc.).

III. Works equally well sitting and standing.

French Bow Disadvantages

I. Difficult to hold properly during the early stages of learning.

II. Weight and sound control are more difficult in the upper half of the bow, compared with violin, viola, cello, and German bow on double bass.

III. Clarity of sound takes longer to develop properly, compared with German bow playing on double bass.

It can often be tempting for teachers to assign the overhand bow to double bassists, simply because it is what other string players are using in the classroom. This does not mean students should not play the French bow, but rather that the clear advantages versus disadvantages must be understood. In two decades of teaching, I have found (as many of you have!) that the most difficult part of using the French bow is learning to hold it properly. This can be discouraging to the student, because it is literally the first thing they have to do! Furthermore, double bassists using the French bow must also learn the correct balance of bow weight and speed, which is different than the violin, viola, or cello. As previously mentioned, bassists playing the overhand bow must rely more on weight than speed when developing a clear sound. This is especially prevalent when beginning French bow players try to create a good sound playing at the tip of the bow. In short, the primary challenges of the overhand bow hold come in the very early stages of learning.

The primary advantage of learning the French bow is that when it is mastered, it is easier to match the bowing articulations of the rest of the orchestra. Most modern bowing articulations and techniques originate from violin treatises; hence, it makes sense for some double bassists to learn the same type of bow hold to mimic said technique.

German Bow (Underhand Hold)

Distantly related to the viola da gamba grip, the German bow hold is the original way to play the double bass. First pioneered by virtuoso Domenico Dragonetti, it was believed that the underhand bow was the only way to “pull” enough sound out of such a large instrument. To this day, many double bass treatises refer to the underhand bow as the “Dragonetti Bow”. The key tenets of the German bow hold are as follows:

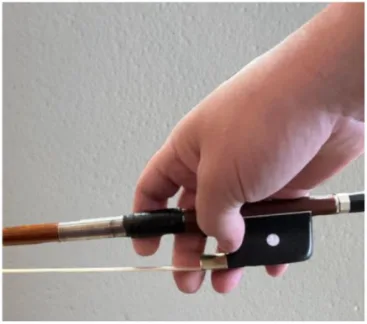

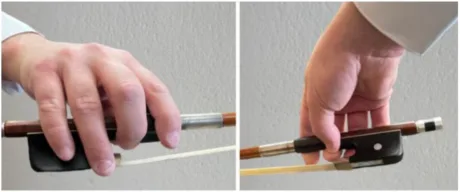

Figure 5. The thumb rests on top of the stick, with the index and middle fingers slightly curled on the front of the stick. The pinky finger rests on or under the frog, near the ferrule.

Figure 6. Some modern players place their ring finger under the ferrule and allow their pinky finger to dangle. This can allow for some greater control of articulation.

German Bow Advantages

I. The textbook German bow grip is similar to the natural shape of the hand.

II. Beginners will produce a good sound on the first day.

III. Weight distribution happens more naturally, allowing students to have instant greater control of bow speed, angle, and position.

German Bow Disadvantages

I. The hold is different from that of the other instruments in the orchestra, hence requiring multiple sets of instructions in the classroom.

II. Modern bow articulations, especially those played off-the-string, can be more difficult with the German bow.

III. Standing and playing German bow can be problematic because the angle of the instrument can lead to the body of the player impeding bow movement.

One of the greatest advantages of the German bow, particularly for classroom teachers, is that it allows students to make a great sound on their first day playing. This can lead to more enthusiasm for the instruments, promoting the chance for longevity of study. While this is advantageous in that it gives the students early confidence with their sound, it can lead to subsequent challenges. As stated earlier, modern bowing articulations are derived from violin treatises, hence they were created with the overhand bow in mind. In my own teaching experience, students who have acquired confidence from starting on German bow often become discouraged with articulation challenges in more advanced repertoire. I have personally found that this issue stems from weight distribution of the bow. While it allows the bow to be pulled across the string with greater ease, the underhand grip does not naturally allow for quick, off-the-string articulation. Dedicated German bow students will overcome these challenges, but usually do so later in study.

Furthermore, many double bassists choose to stand, sometimes because of the lack of available stools! Although it eliminates the need for extra equipment, standing with the instrument can be problematic. Not only do students have to learn to balance the instrument properly (without holding it), playing with the underhand bow necessitates them to constantly rotate the instrument to avoid their right hand from clashing with their bodies.

Final Thoughts

Ultimately, circumstances will often dictate what type of bow is chosen. Sometimes school orchestra programs may only have one type of bow available, or teachers may insist on one bow hold over another because of their own knowledge. My hope is that this article will better inform teachers so that they can make the best decision to ensure the success of their students. As an educator and performer, I have found it to be most enriching to be skilled in using both the French and German bows. While I often play with the overhand bow in modern orchestras (to better match articulations), I prefer the underhand bow for historically informed performances. The French bow allows for quick articulations and ease with string crossings, but the German bow produces a voluptuous sound, especially on gut strings. Perhaps, as educators, we should not ask ourselves “which is better,” but rather “when is it appropriate to use each one?” As advocated by the great double bassist and pedagogue Frederick Zimmermann, I encourage “students to be versed in both schools of the bow, an invaluable technique.”